"Asset Allocator in Chief", in practice

...and a lesson in how f***ing hard org design is as teams scale

Great asset allocation is a make-or-break skill for resource-scarce CEOs and their teams. I hadn’t consciously given this much thought until I read Tomasz Tunguz’s brief and powerful illustration of the idea in a 2017 blog post, which opens thus:

At a recent board meeting, a CEO said, “This experiment will cost $250,000 to run. After three months, we will know whether our new go-to-market strategy is viable.” There’s a brilliance this type of framing. By quantifying the cost of the experiment, the CEO frames company prioritization as asset allocation.

If the CEO is ultimately responsible for a team’s most effective use of 100 chips towards goals x and y, where should we put the chips, and in what concentrations, to maximise our chances of success? Those chips are representative of things like “x hours of y people’s time”, and/or “$Xmn of venture capital”, and/or “$Xmn of revenue”.

However, by conducting the exercise detailed below, I learned that for my team at our stage, the asset allocation model is most helpful not as a practical strategic simulation or modelling tool, but as a sense-check on whether a team is strategically concentrated or diluted as a whole. Tunguz’s piece is short and sweet, so doesn’t touch this critical org design side-effect of making an asset allocation experiment.

Below I’ll walk through how I applied Tunguz’s blog post to Lingumi’s strategy, what I learned, and how that helped us re-assess our organisational structure.

I’ll break this piece out into a strategy question, and 4 key learnings:

Question: does ‘strategy’ beget focused asset allocation?

Learning #1: we were taking too many bets

Learning #2: Org design is f***ing hard

Learning #3: modelling virtual groupings reveals hidden opportunity

Afterword (learning #4): we all want to chop our own spaghetti!

Does ‘strategy’ beget focused asset allocation?

I’ve previously written about using Richard Rumelt’s strategy framework, comprising a problem statement and guiding policy, to narrow down our focus for the year or quarter. Having run on this framework for two years now, I believe that a strategy statement has helped us aim consistently on target, but not dead on bull’s eye.

Strategy statements are built from words. Words leave a lot of interpretative space. In a subjective, interpretative space, ‘having the best rhetoric’ becomes a dangerously effective weapon - the argument that wins is likely to be the best-sounding one (or the HIPPO’s one), but not necessarily the best one.

Let me give an example. At Lingumi, we might look at our quarterly OKRs, and say, “this broadly follows the strategy’s guiding policy, but we’re taking experimental bets here and here outside the core focus because they show high potential and open the door to our brilliant vision of the future.” Heads nod, and you assign assets (time, money) to those bets. I’ve been that voice many times, sometimes to the group’s detriment.

Sometimes, this is the right thing to do! The strategy statement provides core direction, and gives a reason to say ‘no’ to non-core ideas, but doesn’t actually ban them. Indeed, even the narrowest strategies tend to include some allocation of assets (time & money) to non-core innovations or markets. To quote Michael Porter, one of the fathers of commercial strategy, “The success of a strategy depends on doing many things well — not just a few — and integrating among them.” Indeed, multiple models exist to try to theorise how to allocate capital and time across various bets: the McKinsey ‘three horizons’ model, and Eric Schmidt’s ‘70/20/10’ rule, both explained in this summary, suggest allocating the majority of resources to core business activities, technology, or markets, a large minority to emerging activities/markets/tech, and a small but critical sliver to totally new activities/markets/tech, which Schmidt and Google X famously term “moonshots” (that usuall get shut down). Google even has (had?) the famous “20% time” rule to allow bet-taking at the individual level every week, and from which Gmail emerged.

The risk I see with these mental models for early-stage startups, even after gaining substantial initial product-market fit, is that the ‘three horizons’ and ‘70/20/10’ models are both strategic dilutors. I’ll define my terms:

Strategic dilutors are frameworks or activities that inevitably result in the spreading of assets into a wider range of ‘bets’, diluting concentration into a single core activity, technology or market

Strategic concentrators are frameworks or activities that inevitably result in the allocation of assets into fewer, bigger ‘bets’, increasing concentration into a single core activity, technology, or market

I don’t think there is a Myers-Briggs test of strategic thinking, but I suspect most asset allocators skew in one direction here. I instinctively tend towards the dilutor end of the scale, and I’d hazard a guess that lack of focus, i.e. a lean towards dilution, is a more self-destructive characteristic in early-stage startups than tunnel-vision levels of concentration.1

As such I have been working recently on pulling myself in the direction of concentration of strategic thinking. This isn’t a personality transplant - it’s about active learning to improve at my job, which I wrote about last month. I’m also not saying “we shouldn’t make bets / innovate / take big swings”. To abstract away one level, I’m just trying to train my self-awareness, so I can call on the right mode of thought as objectively as possible, rather than instinctively tending towards my dominant traits, and making poorer decisions. I’m trying to add a tool to the toolbox, not replace existing ones.

Perhaps even more important here is building a team - at all levels - who are intelligent, thoughtful, and diverse challengers. My happiest moments are when someone in the team - the more junior the better - writes or speaks in public or private saying ‘I think we’re making a sub-optimal bet here, because x, y and z’. This happens much more rarely than would be optimal, and seems an extremely hard cultural facet to foster as a team grows. That’s for another piece, but this graphic from an NFX piece on ‘Good vs Great Leaders’ struck me as a timely and aspirational:

The Asset Allocator exercise below is the best tool for asset concentration that I’ve experimented with so far. It’s effective because it reduces interpretative space by moving the vector of debate from words to numbers, counter-balancing rhetoric with (greater) objectivity. I also learned that it’s a great tool for analysing one’s org design, and whether it genuinely empowers teams to make autonomous strategic decisions. Lastly, doing this was a healthy lesson for me in how much I need to learn and grow to improve as our CEO.

The Asset Allocator Exercise

Heading into planning Q2 ‘21, we’d been discussing whether our Q1 chips had been spread too thinly. There were symptoms of strategic dilution coming from the team: we had a lot of OKRs, the average squad size was small (one pizza, not two), some team members - especially some developers - were feeling too stretched or isolated to best accelerate their squad’s output, and teams were feeling siloed. I was pleased that we were being reasonably open about these challenges across the team, but it felt like we were reacting a quarter later than we could have done. Hindsight is 20/20! However, to slightly mis-quote Mercedes Bent at Lightspeed, I want our whole team, particularly our senior team, to be self-reflective “learning animals”, listening and reacting fast to our own weaknesses rather hoping to be perfect planners from day 1.

Learning #1: we were taking too many bets

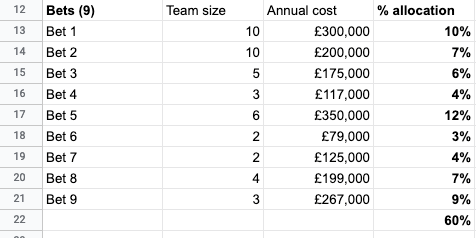

To try to quantify this set of feelings and the qualitative feedback being shared, I decided to tackle the asset allocation exercise. The pareto principle definitely applies here: an hour of napkin maths got me to 80% of the detail, which was sufficient to inform decision-making. I took our headcount budget, broke it down quickly by approx cost per squad and department, and then converted each to a % of total headcount cost. To give a high-level sense to readers, there are about 60 people in the team at time of writing, but I’ve replaced the Lingumi numbers and names with dummy data in the images used below.

I started with department/function costs, eg “Tech” or “Marketing”. These are the largest organisational categorisations at Lingumi:

This didn’t pack many strategic surprises, but gave me an eyeball check of costs per teams, average salaries per function, etc etc. I suspect most readers will know those numbers already for your teams, but handy to run this layer if not.

I then broke this down into our smallest company category, the cross-functional ‘bets’, a.k.a. squads. This was a bit more manual - I checked composition of each squad or working group against our payroll, and compiled the equivalent annual cost per “bet”. This sounds long-winded, but I did it roughly, on the back of an envelope, as that yielded a sufficient 80/20-style level of detail. Again, I’ve replaced all the numbers with dummy data, but it looked something like:

The feeling of strategic dilution amidst the team was translating in the numbers: we had 9 groups working cross-functionally on “bets” of one shape or another, and some of those were composed of only 2 or 3 people. While many people had been working across 2 bets, we were clearly stretched thin, allocating fewer critical resources - especially development time - to each “bet”, and detracting from the core. This was reflected in the plethora of OKRs that had been set, too (…what’s the collective noun for OKRs? An ‘overwhelm’ of OKRs perhaps?)

Learning #2: Org design is f***ing hard

This number of experimental units COULD be perceived as highly strategic: lean units, hungrily chasing opportunities that can be tested within a few weeks, might be optimal to keep up the pace and autonomy. I’d initially perceived it as many couples dancing on the same dancefloor - each has their own effective dance, yet avoids bumping into the other. Some companies take this route, but they tend to be larger companies with ‘business units’ like Amazon, and Spotify nowadays, or gaming companies with per-game teams.

For Lingumi, it was feeling sub-optimal. As I thought about it, my mind went to four prior inputs that I have in my notes (see last month’s piece for more on my note-taking approach) and which, as a grouping, made me think that this structure was not suitable for Lingumi right now:

Snowflake CEO Frank Slootman: “when designing the org, don’t let yourself become mile wide, inch deep”

Etsy CEO Josh Silverman: “at Etsy, when planning, we ask ourselves, ‘what are the fewest things we can do while ensuring we still achieve the goal?’”

Former Farfetch COO Andrew Robb: (gentle mis-quote!) “individual business units shipping independently to the same platform is the ideal strategic outcome, but it cannot be backed into - the platform-building work to enable this takes years of deliberate, expensive asset allocation”

Varun Srinivasan, Director of Eng at Coinbase: “Push strategic thinking down the organisation around the 50-person point, before it gets too big”

The team and I all started to feel like our number of bets was mile wide, inch deep (1). We were trying many different things (2). We don’t yet have the platform to support many teams shipping to the same parts of the platform fast (3).

But what felt most painful was that we’d inadvertently failed to push strategic thinking into the team (4), i.e. empowering genuine autonomy. Instead, we had accidentally set a top-to-bottom strategy at the top of the organisation by designing for small squads with individual areas of focus. In other words, to return to an old theme of mine, we were dictating the ‘how’, and not setting a clear enough ‘what’. Squads had choice over how to work and what exactly to ship, but the team as a whole didn’t have the sense of freedom to debate how to tackle business goals and objectives, and then divide itself formally or informally following this process of debate, trade-offs, and buy-in.

The lack of autonomous decision-making, resouce scarcity, number of goals, and clashing priorities was having a second-order effect on some people’s mental health, too, as the “stretch” is not spread evenly. That, if nothing else, was a wake up call for me. Our mission is insanely big and important to me and the team, so burning out team members over >1 quarter was not territory I wanted us to be in, and I feel cupable. It would have been ruinous to the long-term success of Lingumi, and to individuals in the team whose lives I want to be enriched, not damaged, by joining the mission.

Learning #3: modelling virtual groupings reveals hidden opportunity

Tunguz includes this crucial line in his piece: “there’s a hidden cost, the opportunity cost. What could we do with those teams' time if we don’t pursue that [bet]?” The feeling of overload or being stretched too thin was simultaneously putting pressure on the core activities where successful delivery for our customers is most critical.

If we changed our method, and set higher-level, bigger business groupings and goals, then let teams decide how to allocate their time to those, would we end up investing more time into the core, mission-critical objectives or part of the product? Would we reduce the feelings of stretch and resource scarcity? Would Lingumi families get a better teaching experience?

To sense-check the idea, I boiled the bets down into larger virtual groupings with shared customer or business problems to solve. This reflects problem-focus, rather than current people divisions. I added ‘Core’ or ‘Experimental’ to each depending on whether we’ve proven them out yet. On top of that, I added the amount invested to date, based on number of months that we’ve been running the bet. I’ve replaced the real data with some dummy numbers again:

What did this tell me? First, two superficial but reassuring observations:

~60% of our headcount ‘assets’, ie team time, is being invested into our customer-facing “bets”, and 40% into critical enabling functions that customers don’t see, like Finance, Ops, HR. The numbers above are replaced with dummy data, but that is roughly accurate. Seems sensible, though I have not gone benchmark hunting.

66% of work on customer-facing problems is spent on proven, or “core” problems or products, and the vast majority of expenditure to date, by comparison to the Experimental group. Again, lacking any benchmarks, this seems fairly sensible.

More striking, though, is a third observation: this list is a LOT shorter than the list of 9 squads above. At a management level, we’d sliced and diced the team down from these groupings into smaller sub-groups. I think we’d implicitly settled on a Q1 plan with “max coverage” rather than “max focus” or “max autonomy”, all three of which are somehow sub-optimal, but, to abuse a Tolstoy line, each sub-optimal in its own way.

Which might have been most optimal? To return to the Tunguz line above, if we’d sat down with all the people represented above by ‘Core Bet Group 2’ and said “right, we’re betting £250k on you as a group to solve problem X for customers, you figure out the how!”, they would have been empowered to focus on 3/4/5 bets or 1, to create smaller sub-divisions or work as a single larger team, and to own the successes and failures of those decisions fully and iterate fast mid-way if needed. That would have represented “pushing strategic thinking down the organisation”. It might have gone terribly wrong, but I doubt it - we’ve got a strong team, and the individuals doing the decision-making would have been the closest to the problem, and so, I hope, have made really strategic choices.

Without going into the weeds, that’s closer to where we’ve landed for our new quarter, though we’re not all the way there. Planning is hard, isn’t it operator-readers?

Afterword (learning #4): we all want to chop our own spaghetti!

As a kid I hated it when I got spaghetti from the children’s menu, and it arrived chopped up into smaller pieces. How insulting! I’m eating the spaghetti - shouldn’t I choose if I want it chopped up?!

If, like Buster Keaton, I’d been given a bowl of spaghetti, and opted to go at it with scissors, I’d have felt totally different. Empowerment! Agency! Strategy! Whether my decision had been successful or not, it would be my decision.

In asset allocation and organisational design, this isn’t a one-person decision. A group has to decide collectively if they want to chop their spaghetti up, or get out a spoon and go Italian with it. Some will disagree, but in an empowered team, all will commit, because its the team’s decision.

Reflecting on Q1, and watching as we iterated during Q2 planning, is that we’ve probably made steps towards improving both our asset allocation and our team’s feeling of strategic empowerment. We can’t be right each time, but we can learn fast. Three months ago, we’d handed our teams a plate of chopped up spaghetti. We’re in a new quarter now, and allocating fewer, bigger bets, empowering teams to make decisions within those. Harder, but even more importantly, we’re working on moving from starting with how, to starting with what, identifying core customer and commercial problems, and handing those to brilliant teams to figure out how to tackle. In other words, no more chopped spaghetti.

It may take time and cause new forms of chaos, but that’s part of the fun. Reacting isn’t painless. Moving from dilution to concentration hurts. It means putting emerging new ideas in the fridge, or pausing development of features gaining traction to return to accelerating the core. I find this as painful as those working on them, because I love those big bet new ideas, and tend to favour the innovation side of the 70/20/10 instinctively…

But part of my job is to constantly steer myself (…and then the team!) back to the mission, to remind myself and everyone in Team Lingumi that a more focused strategy is probably more likely to help us achieve it, and to empower the teams to take ownership over how to attack the problems. More success now = more assets later to invest in these exciting bets, without diluting the core.

For an exploration of what goes wrong when defensiveness, fear, or tunnel-vision become all-encompassing at scale, Jim Collins has some excellent examples in ‘How the Mighty Fall’

Another corker. Great work 🙌

How would you adapt this for a team 1/10th the size (Or an earlier version of Lingumi)? Or was it just less of a problem with fewer resources? We have multiple quarterly goals with a small team, which probably just subdivides time within people rather than teams.