What on earth is a virtual mentor?

What UiPath, Homer's Odyssey, and Jeff Bezos have taught me about mentorship

Last week I read a line in Mario Gabriele’s deep-dive into UiPath that made me think in a completely different way about the nature of advice and mentorship. Gabriele quotes Daniel Dines, the Romanian founder of the newly public UiPath, looking back on the inspiration behind their pivot from software outsourcing shop to $35bn “RPAaaS” (yes, that’s ‘robotic process automation as a service’) platform:

Whatever you think about Dines and UiPath, there’s something extremely inspiring about a non-native English speaking Romanian founder, based in a former Soviet state, without a local startup ecosystem, angel investors, or easy access to early-stage venture capital funds, adopting Paul Graham as his mentor. Mentorship is a term that always felt a bit abstract to me, but Dines’s attitude changed my mind. I found two things about his comment thought-provoking.

Firstly, Dines seemily uses the word mentor quite deliberately. He doesn’t describe ‘reading a post by Paul Graham’ or call Graham an ‘inspiration’. He implies a quasi-active relationship, a sense of commitment to how Graham thinks and how that thinking shapes Dines. It’s uni-directional, but impactful beyond the level of ‘advice’. Secondly, he is his ‘virtual mentor’, both in the technological sense (Dines is adopting Graham as a mentor from a great distance, in a way that the internet and software make feasible at exponential scale) and the formal sense (Graham has not opted in to this relationship, except that by writing publicly, he is hoping for his pieces to be useful and motivational to founders beyond the narrow YC cohort pool who used to get those thoughts on tap.)

I admire this hugely. Dines didn’t settle for a less-experienced, local mentor while setting up his startup, nor did he wander around at a loss. Instead, much like UiPath’s software does, he assimilated existing content and tools to get the job done at an acceptable quality level, adopting Graham as his virtual mentor.

What is a mentor?

I instinctively dislike the word ‘mentor’. It’s so widely (mis)used, and 90% of the time I hear it, I am sceptical about the depth or impact of the relationship. As a former EF founder, I’ve recently been asked to mentor newer EF founders, and was contemplating what I was supposed to do to fulfil the request. It feels so abstract.

I know what mentoring is not. Mentoring is not (just) giving advice. Dines says of Graham, “he deeply influenced my thinking”. Advice tends to be short-form, transactional, omnipresent, prescriptive, and often generic. It usually does not deeply influence one’s thinking. Advice can also be good, but delivered inappropriately - some of the best advice I’ve ever had was right, but at the wrong time. Advice is part of a mentoring relationship, but only a sub-section.

Mentoring is also not coaching. I have learned both empirically (from working with an executive coach), and conceptually (from reading some of the theory behind transformational coaching) that coaching is a formal relationship based on the “expectation of the achievement of shared goals, and a solid commitment to planned action”1 to quote Kerryn Griffiths (linked above), and usually focuses on developing behaviours (like growing “self awareness, developent, inherent creativity and potential”. My coach deeply influences my behaviours, but she is not my mentor per se.

A brief history of Mentor(s)

The concept of mentorship has been fuzzy since day 1. Indulge me while I dig into its history briefly…

The origins of the word trace back to Homer’s Odyssey, where Mentor is the name of a character chosen by Odysseus to oversee his son during his absence when he sails off to Troy. Mentor turns out to be rather bad at his job, ironically. As one of the servants observes upon Odysseus’ return, “Odysseus has come home, and high time too! And he’s killed the rogues who turned his whole house inside out, ate up his wealth, and bullied his son.” Like many self-styled ‘startup mentors’, I suspect a capabilities assessment had not been conducted thoroughly here. Perhaps Odysseus was not thinking long-term enough; the Trojan War, like the archetypal startup journey, took 10 years to fight.

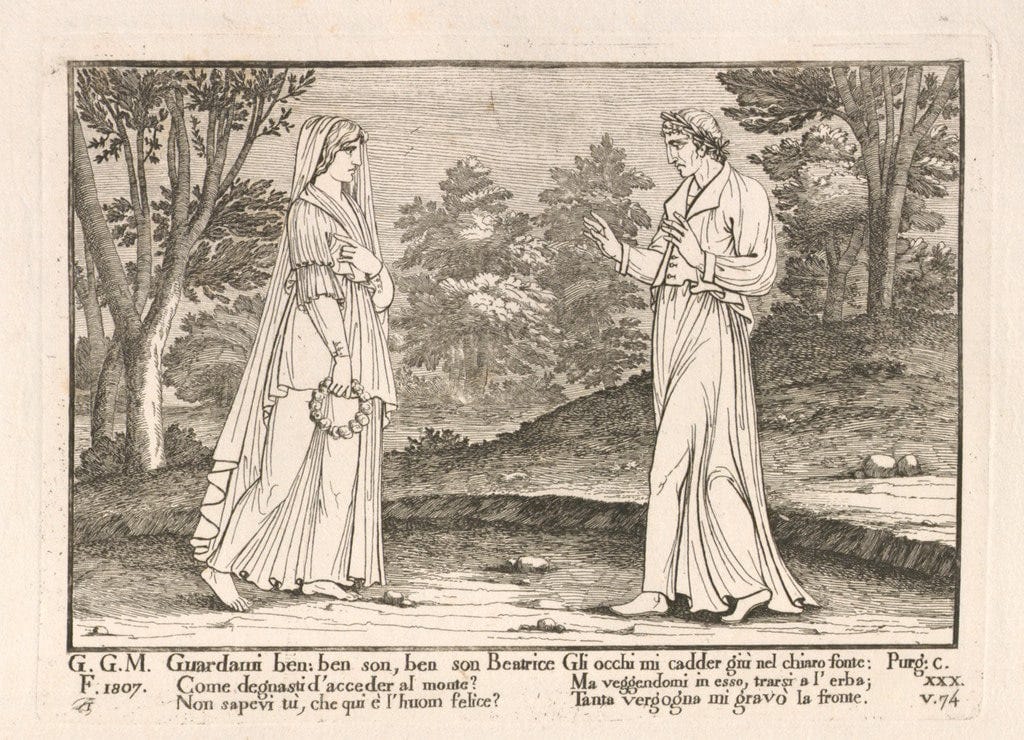

Despite being founded back in 1194 BC, the role of mentor appears not to have been formalised to the same extent as ‘coach’. Academics seem to mostly fall back to synonyms, suggesting that Mentor - and all mentors since - exist to serve some mix of “counsellor, teacher, nurturer, protector, advisor and role model”2. My favourite definition of mentoring comes from Laurent Daloz, who, writing in the higher education journal ‘Change’ in 1983, described mentors as being like a guide on a journey, carrying out three duties: “(a) pointing the way, (b) offering support, and (c) challenging.”3 A coach can do (b) and (c), but a good one will deliberately not do (a), working to help you do that yourself. A loved one might do (b) but perhaps not (c) or (a). A typical venture capitalist will claim to do (b) a lot on their website, then spend a lot of time doing (c) and a bit of (a), possibly in the wrong direction but with buckets of confidence.

A great mentor does all three for founders, and, like Virgil guiding Dante through hell and purgatory before stepping aside to let Beatrice take over as guide for the paradise leg of the trip, knows when their time has come to step away.

A mentor, whether virtual or real, needs to be an opinionated, challenging, supportive guide. They also, I think, need to be a fairly omnipresent guide, their voice in your mind at many a key moment. Dines does not just read general startup advice, including that of Paul Graham - I infer that he is a disciple of Graham, treating him amongst a small group whom he weights heavily in his mental hierarchy of advisors.

Adopting a virtual mentor

I love how radically the idea of virtual mentors improves both the access to, and the quality of, mentoring.

On the matter of access, anyone can adopt Graham as their virtual mentor, not just the Silicon Valley elite. The internet has made content distribution possible, for free, at massive scale. Some of the best thinking on any given business topic is now accessible to anyone who wants to learn from it. You can use YouTube, his website, and Google to build a fairly complete, portable, pocket Paul Graham that squawks things like “do things that don’t scale” and “don’t let your vision get in the way of listening to users” into your mind in moments of doubt, indecision, or fear. Graham, virtual or real, is a motivating teacher. This is a theme we care about a lot at Lingumi, where we’re trying to make the world’s best teachers, and teaching, accessible to children at exponential scale. One of the great wonders of the technology age is democratising access to, and reducing the cost of, teaching.

On the matter of quality, virtual mentorship holds the potential for enormous quality improvement compared to ‘real’ mentoring. Your likely pool of ‘real’ mentors, unless you’re in the tech world elite or a prolific networker, is quite limited, and the quality very mixed. I remember going to tech accelerator “mentoring days” where a bunch of accountants, lawyers, and, woe betide, self-described, LinkedIn-listed ‘startup mentors’ would charge in, spending three minutes with each startup to throw ideas, advice, or worse, criticism, at the founders. Compare that to Graham’s decades of experience and the thousands of startups he’s watched boom or go bust. The contrast, even if the virtual Paul Graham (often nicknamed ‘PG’) is only 10% as effective as having him as a physical mentor, is stark. YouTube member Gaurav obviously agrees (and has read PG’s advice on writing simply…):

It’s possible to criticise my zeal for virtual mentors by saying “this is just reading online advice”. That misses the point. Reading advice would mean ingesting a line from Graham into the sorting hat in your head, and letting your advice algorithm weight it fairly evenly alongside thousands of other bits of advice, and attempt to store it somewhere in a mental drawer. Graham would be one of many, floating in a sea of synapses and grey cells.

Adopting a virtual mentor means becoming obsessed with that individual’s way of seeing the world. It means the dedicated pursuit and absorption of their advice. If Paul Graham is your virtual mentor, Paul Graham is the loudest voice you hear when trying to decide how to build a product, or talk to customers, or raise money, or whatever topic you have chosen Graham as your mentor on. It means you usually trust their take on a topic, however controversial, and stand by it in the face of the 5-10 conflicting opinions you might hear from others who are not your mentors or whose opinion you do not hold as high in your regard. That’s what you’d do if you had Graham as your physical, real-world mentor who you met weekly, no? If not, why lean on them as a mentor?

One other value I see in virtual mentors is that you can expand your total pool of mentors, because the time-to-value is very short and the topic-specificity is higher than with a real-world mentor. I don’t have a dedicated real-life business mentor (though I do lean on some investors or board members in a mentoring-style relationship), but I’d need to have a lot of time with them to build the relationship, and find someone who was extremely strong across the board. it’s not impossible, but it requires careful selection and time investment. To quote Elvis, only fools rush in.

By contrast, finding virtual mentors feels a bit like playing fantasy football: in a world of virtual mentors, you can pick Elon Musk as your idea generation mentor, Katrina Lake for strategy for a data-heavy business, Reid Hoffman for fundraising, Emily Weiss for brand for a D2C business, etc…and then bore deep into each of their brains thanks to the proliferation of interviews, books, and podcasts in which they’re accessible if you decide to really assimilate that individual’s way of seeing the world alongside your own.

My virtual mentor(s)

I wrote previous about how I learn to be a better CEO, which covers how I capture notes from the stuff I read and listen to. Looking at the names that pop up regularly, I see two groups: those whose ideas I find thought-provoking, but would not adopt as virtual mentors, and those I’d call virtual mentors.

For example, I have written previously about Daniel Ek and Spotify’s strategy, and read a lot of his writing, and writing about him, but don’t consider him a suitable virtual mentor for where I am now. There isn’t an obvious red thread to Ek’s way of thinking that fits my mentoring needs at this stage. I do hope he one day reads my article about him above, though. Likewise I am a great admirer of Katrina Lake from Stitchfix and her dedication to the use of data in the business from very early in its path, and of Tobi Lütke from Shopify and his Starcraft-inspired approach to strategy. They are only 12 or 13 years older than me, and I aspire to their levels of success at bringing their visions to massive scale. Their businesses and strategic landscapes, however, are too far removed from Lingumi’s to place them in that rank of virtual talking heads in my mind as I go about my job. More extreme would be Steve Jobs; I am of course deeply impressed by what Jobs created, and he has many dedicated acolytes, but his world view and way of leading feels so far from my own, that even had he been my real life mentor, I suspect I would have found it jarring.

Jeff Bezos, on the other hand, is someone I feel has inadvertently become a virtual mentor, though I hadn’t framed it like that in my mind before reading Dines’s comment. I suspect I am not the only one to feel this way about Bezos. While controversial, he’s an extra-ordinary CEO. I’ve read just about everything written by or about Bezos that I can get my hands on. Amazon is a million miles from Lingumi in terms of size, vision, business structure, and logistical complexity. However, his approaches to long-termism, free cashflow, leadership characteristics, team structure, and even trying (and failing) to improve performance measurement all stick in my head, sometimes because they resonate with my strengths or natural instincts, and sometimes because they exhibit strengths in areas where I am weak, and trying to improve. To me, this is the test of a virtual mentor, in the same way as you might test the robustness of a ‘real’ mentoring relationship: how persistent in your head is that person’s voice? I think I hear the voice of the virtual Bezos in my head more than any other individual business strategist or leader I’ve studied. It’s a bit of a corny Bezos-ism, but I often feel guilty when I spend money on office furniture, because I picture Bezos and his hand-made door desk:

While Bezos doesn’t sound like an especially charming man to work for, and there are a lot of negative sides to his controversial leadership style that I would not contemplate mirroring (Exhibit A: line 6 in the infamous 2002 API memo), he has become embedded in my brain. Bezos is my version of Dines’s squawking virtual Paul Graham. At a board meeting recently, I was given some feedback about being so long-term and mission-oriented, that I was under-weighting the importance of shorter-term opportunities for growth. I took the feedback to heart - it contained a fair and actionable suggestion of how I could lead better for the short term. However, I did simultaneously have Bezos’s 1997 shareholder letter ringing in my ears: “It’s all about the long term”.

If Bezos were my real-world mentor and we met for coffee each week, I’d imagine he’d say the same things that I hear in my head from the virtual Bezos - focus on the long term, keep the business lean and frugal, find and track leading indicators, invest boldly in future cashflows over profitability, develop a culture of truth-telling and writing rather than bullsh*t and powerpoints, and so on. He seems to be a pretty consistent man, which makes him easy to follow as a business disciple. I don’t take all of that advice as well as I might, and in some cases, might choose to ignore it if it didn’t fit my leadership or business needs. But it’s there, it’s omnipresent, and I weight it very heavily in my mental sorting hat. I return to a PDF of that 1997 letter frequently in moments of doubt, and enjoyed re-reading for the 50th time it as I sat down to write this.

As I reflect on Dines’s comment, I realise how often Bezos, and a select group of other mentoring voices, real and virtual, recur in my thoughts as I make, and test, decisions. If you haven’t developed a real or virtual mentoring relationship, find a business leader or executive you resonate with, and go down the rabbit hole.

—

P.s. I’m aware that my writing style is quite long-winded. I hope it doesn’t put you off reading these. Perhaps I should adopt PG as my writing mentor?

Griffiths, K. (2005). Personal coaching: a model for effective learning. __Journal of Learning Design__, 1(2), 55-65. http://www.jld.qut.edu.au/

"Homer’s Mentor: Duties Fulfilled or Misconstrued?”, p3, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242760920_Homer%27s_Mentor_Duties_Fulfilled_or_Misconstrued

Daloz, L. (1983). Mentors: Teachers Who Make a Difference. Change,15(6), 24-27, in Anderson and Shannon, “Toward a conceptualization of mentoring”